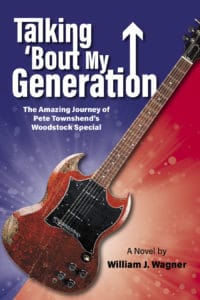

Talking ‘Bout My Generation is a brand new novel by William Wagner. It’s available for pre-order right now, and ships the week of August 18th. The novel is an imagining of what happened to Pete Townshend’s guitar from Woodstock after he tossed it into the crowd. We caught up with him recently to chat about the book.

EP: The genius of Talking ‘Bout My Generation is the premise of the book, the journey taken by Pete Townshend’s guitar after he tossed it into the crowd at Woodstock. When did you have that Eureka moment, and did you know immediately that you had something special here?

Will: My Eureka moment came several years ago, although I’m ashamed to admit I don’t recall the exact details of when the lightbulb went on in my head. As far back as high school, I had been struck by the image of Townshend tossing his guitar into the crowd at the end of The Who’s set at Woodstock; decades later, it occurred to me that a great fictional odyssey could spring from that act. After having my Eureka moment, I wrote the prologue—the jumping-off point for my story. And then I let the prologue sit for about a year as I thought about the journeys—the situations and characters—that would best exemplify my idea of Townshend’s Woodstock guitar as an enduring symbol of hope. Like the guitar itself, most of the people in the story get battered in one way or another during their life journeys, but they keep on keeping on.

EP: It turns out that Chicago and its surroundings play an unexpectedly important role. Why did you make that choice, and for those people here in the area, what are some of the Chicagoland areas that show up in the book?

Will: They say you should write what you know. And since I’ve lived in the Chicago area for most of my life, I know it well. Plus, Chicago is one of the greatest, most authentic cities in the world. And it’s also a little off the radar compared with cities like New York, Los Angeles, Paris or London. In my mind, it was the perfect place for this guitar—this lost piece of history—to be stashed away for a while.

Among the pieces of Chicagoland that show up in the book:

• The old Chicago Amphitheatre on the South Side

• The outdoor concert venue in Tinley Park (known as the World Music Theatre when it appears in the book)

• Wrigley Field

• Walker Bros. Original Pancake House in Wilmette

• The Chuck Wagon, a greasy spoon in Wilmette that is legendary in that neck of the woods

• The Italian restaurant Convito Italiano in Plaza Del Lago in Wilmette

• Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago

• The Hilton Chicago on South Michigan Ave.

• Jewelers Row in Chicago

• Oakton Community College

• The Kane County Flea Market

• A fictional tattoo parlor in Uptown in Chicago

• Arlington Heights (the main character works at the Daily Herald newspaper)

• Evanston (the main character and his wife live in Evanston)

• Winnetka

• Glenview

• Lakeview in Chicago

• Lincoln Park in Chicago

• The Fox River out by McHenry

And there are lots of other nods to places around Chicago. This is, in many ways, “a Chicago book.”

EP: It’s pretty obvious that you are a huge rock and roll fan. That comes through clearly in this book. What did that music mean to you, and how did that translate into the various different elements of this story?

Will: Music means everything to me, even though I spent a chunk of my career as a sportswriter. The music from the Woodstock era is particularly meaningful to me, because the best of it had a boldness—a bravado—that made you think it could bring about real change in people’s lives individually and in society as a whole. That hopefulness is central to the book’s theme. The power of music permeates the entire book. It is, after all, a guitar—and Pete Townshend’s from the most mythological music festival ever—that binds the various stories and characters together.

EP: I love that Pete Townshend himself, a fictionalized (but totally believable) version of him, is one of the main characters. How much did you know about him and the Who before you started writing, and how much research was necessary, because you really get into the nitty gritty of Pete’s past and prickly personality.

Will: I did a ton of research to create the fictionalized Pete Townshend. I read and listened to scores of interviews with him to get a real feel for his speech patterns and for his temperament away from the stage. Luckily, Townshend is one of the most talkative guys in rock history, so a lot of interviews are out there from which to paint a fictional portrait. I also heavily researched points in Townshend’s life and The Who’s career that appear in my novel to ensure I’d get certain facts right. Otherwise, none of my fictionalized elements would ring true. One thing I didn’t do was read Townshend’s autobiography, which was published while I was writing this book. I didn’t want Pete Townshend’s vision of Pete Townshend to cloud my vision of Pete Townshend.

EP: This book comes out during the anniversary week of the original Woodstock. The first chapters of this book take place there at the festival and its surroundings. It seems so real to me, I just assumed you were there. Then I saw you were still a little kid at the time, so obviously you didn’t attend. What did you learn about Woodstock that you didn’t know when you started this process?

Will: Here’s another area where I did a ton of research. I read as many personal accounts as I could from people who had been there, dug up old articles on the festival to develop a sense for how it was being perceived at the time, and studied maps and such in order to literally get the lay of the land. In my research, one of the more peculiar things I learned about Woodstock—and it’s the tiniest tidbit—is that the organizers built a playground for the children who might be there. To me, that perfectly summed up the naïve idealism of the event and the hippie movement in general. The organizers came up short on so much of the big stuff—food, toilets—yet they had a playground for kids, of whom there obviously were very few. All at once, it was a beautiful and misguided gesture.

EP: Tell us a little bit about you, Will. What’s your background, and why are you the right man to write this book?

Will: I’ve spent virtually my whole career in publishing, both as a writer and editor. It’s certainly not the easiest way to make a living, but there’s nothing else I’d rather do. I was a Creative Writing major at Knox College and the editor of the school’s literary magazine, Catch, my senior year. Upon graduation, however, I decided that I also liked to eat, so I maneuvered from writing fiction to journalism, where one can at least eke out a living. Yet I’ve always had fictional stories floating around in my head. I’m the type of person who likes to watch people at, say, an airport and imagine lives for them. So in a sense, I feel like I’ve come home with this book after a lot of years in the wilderness. I had something to say, and I believe I said it in a way that will entertain, amuse and give folks some hope.

Dod Pete read the book and did you get any feedback